Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec: Two Songsheet Covers

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose small stature was easily recognizable, was a well-known figure of Parisian night life and its musical and entertainment scene. While he is today best remembered for images of cancan dancers, café-concerts (dance halls), prostitutes and all manner of party scenes, Lautrec also frequently attended the theater, musical performances and the ballet. In his work both depictions of high art forms and lowbrow entertainment can be found. It can easily be argued that Toulouse-Lautrec did not really differentiated one from the other.

Beyond looking for fun, which he was known to do, and beyond looking for inspiration for his art, he mostly sought friendship and acceptance. His physical malformations and limitations, which were the genetic consequence of frequent familial intermarriage, were hard on him emotionally. Henri could not easily partake in the boisterous play of youth; and even activities such as hunting and horseback riding, valued by his upper-class upbringing in a family of nobility, were hard to join in earnest for him.

Upon arriving in Paris, Lautrec shed the decorum expected by this family and was thus able to push these physical limitations aside. Lautrec became the proverbial life of the party. Encounters and friendship came to him easily and he sought acceptance and appreciation wherever he could find it. One such friendship was with the bassoonist and composer Désiré Dihau (1833-1909).

Dihau was famous in Paris. He played for nearly 20 years at the Opéra de Paris, and also performed with the orchestras of the Théâtre-Lyrique and of the Théâtre des Bouffes-Parisiens. Not content with just these engagements, the workaholic also performed solo bassoon pieces at the Eldorado, the Cirque d'Hiver, the Orchestre Pasdeloup and at the Théâtre du Châtelet for the Concerts Colonne.

Because of his many engagements Dihau became known to many artists around the capital, including Edgar Degas, who painted his portrait and depicted him in other compositions. Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, who was a distant cousin or nephew (the exact relationship is unclear), would have encountered Dihau at one of his many performances soon upon his arrival in Paris.

By the early 1890s, Dihau, now in his late fifties, was performing in orchestras less often and had more time on his hands. He filled it by composing melodies for friends, such as the poet Jean Richepin (1849-1926). Dihau’s scores, fourteen of them, which would have been performed in various venues, including possibly at Le Chat Noir cabaret, were illustrated with covers by Toulouse-Lautrec.

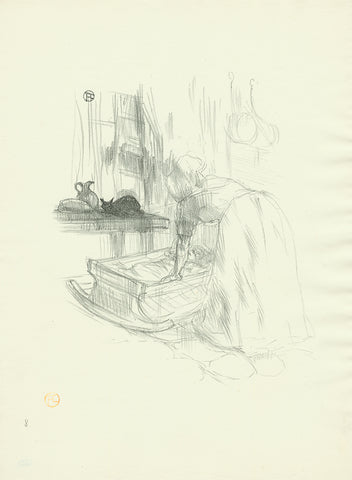

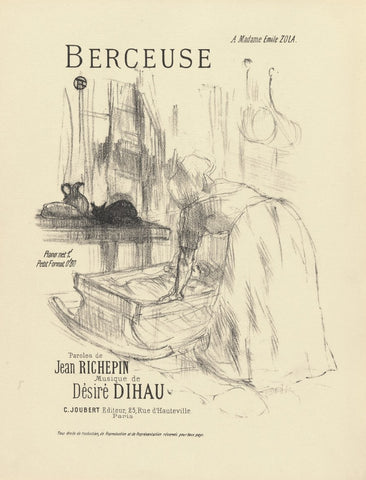

We have two lithographs drawn by Toulouse-Lautrec for the Mélodies by Dihau. The first is titled Berceuse (Lullaby), and depicts a woman bent over a cradle (See it in detail HERE). She seems to be using the weight of her upper body to rock the cradle to get the baby to sleep. The poem was created by Jean Richepin in 1881. It is unclear exactly when Dihau scored it. The text mostly contrasts the cold outside with the peace and quiet of rocking a baby to sleep. Toulouse-Lautrec didn’t use this contrast. Instead he depicts the homely quiet of a mother keeping her young child quiet, while she tends to other chores in the kitchen. Two pans can be seen hanging on the right, while bread and water (or is it wine) are resting on the table; ready to be served to the family. A cat is also lying on the table in what is likely the warmest room in the house. The woman, who doesn’t show her face, is dressed in short sleeves, further suggesting the heat of the kitchen. Thus Lautrec evokes the warmth of the hearth and the bliss of mother and child at peace.

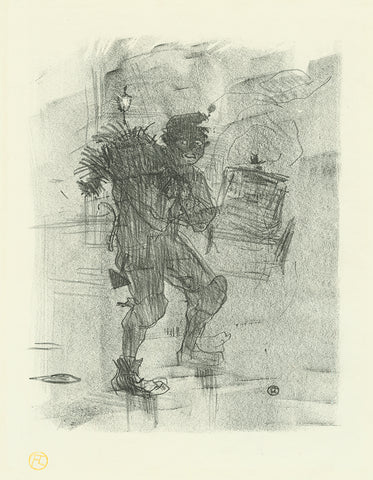

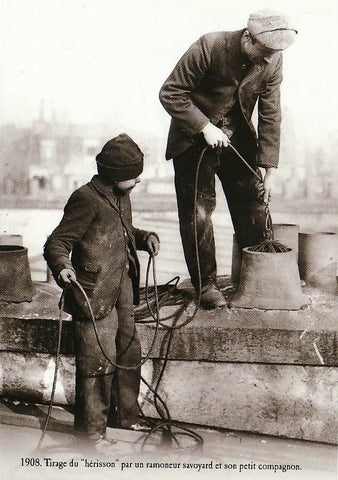

The second lithograph is titled Ballade de Noël (Christmas Ballad) and depicts a chimney sweep (ramoneur in French) at the end of a work day. In modern France, with the advent of the use of coal as a source of energy, the modern convenience required regular cleaning of chimneys. This became particularly critical in multi-storied dwellings. Climbing on the roofs was a perilous undertaking.

This task was generally reserved for young boys from Savoie, who had time to do it in winter, when farming jobs in the mountains came to a standstill. They would appear in cities at the start of winter and be gone by spring. They were easily recognized by wearing floppy red hats with a tassel. In wide chimneys very young boys were sent down to scrape the soot off the brick walls. This practice was extremely toxic. Upon realizing the mortality of boys at very young ages, and as the profession modernized, this practice was replaced with tools which were used to scrape the conduits without having to go down it.

Brushes, generally attached to long poles, were pushed down to bring the soot into the hearth, where it could easily be picked up and carried off. Our ramoneur is young, perhaps in his mid-teens and is carrying a brush (named le hérisson in French; literally translated, the hedgehog) on his back, as well as a typical triangular tool at his hip (likely used for scraping). He still has his knee pads tied around his legs and is probably headed home. His face is black from the day’s work, and his expression seems to suggest he’s seen something spooky. Richepin’s text, which Toulouse-Lautrec was illustrating, asks for a thought for those who do not have a hearth at Christmas time. Perhaps Lautrec wished to show hardship on the face of the young boy, rather than fear. A ray of brightness shines from the gaslight in the background. Lautrec literally scraped the stone to obtain this spark of light. Also in the background, a horse drawn carriage is careening into the night. Did it just miss the boy, and it perhaps that what spooked him? No matter; the carriage’s drunken tilt also aptly evokes the young man’s weariness at the end of what must have been an exhausting day.

Our lithographs were eventually completed with typographic text (with letters), which listed the author, the composer, the title of the song-poem, as well as the publisher of the score. Interestingly, one of these scores is dedicated to the wife of Emile Zola. The connection is unknown. The editions with letters as song sheets were of 500. As the ephemera that they were, the printing of these editions is rather poor and also on cheap paper. They have become rather scarce, because they were used as a piano score, but also because of cheap production made them brittle. As with all of compositions in this series, Lautrec printed a very small edition of the lithographs before letters were added. Ours are one of 20 impressions only, printed as soon as Lautrec had drawn them on stone. It is as close as we can get to the hand of the artist at work. These first printings were not marketed, as far as we know. They would have been printed for Toulouse-Lautrec’s personal use. He signed each impression with his monogram stamp, and numbered them in pencil. Lautrec likely gave these impressions to close friends and collaborators, or sold them to his most admiring patrons. Early impressions like these are extremely scarce and are amongst Lautrec’s most desirable monochromatic graphic work.

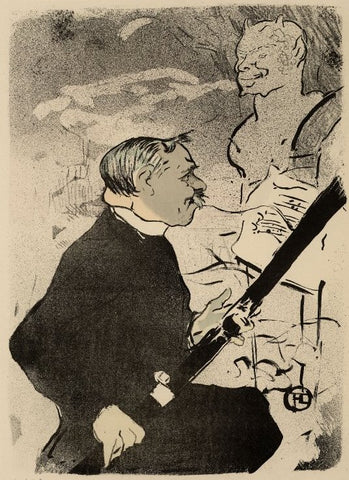

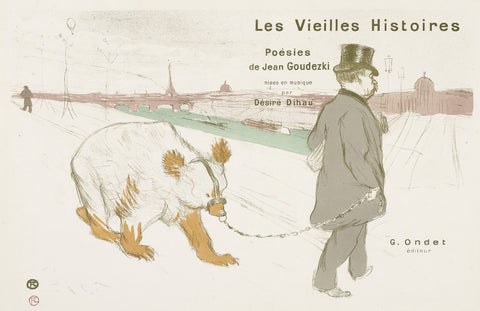

The collaboration between Dihau was clearly successful. In 1893 Lautrec also illustrated the cover of the Vieilles Histoires, a collection of poems by Jean Goudezki, set to music by Désiré Dihau as well. In this color lithograph Lautrec represents the musician, his bassoon tucked under the arm, leading a bear by a leash to the Institut de France via the Pont des Arts. And Lautrec further depicted Dihau in a number of other lithographs, drawings and paintings.

* * * * *

Fait froid dehors,

Ça glace l’sang.

Mais gna d’chez soi

Qu’ pour ceux qu’a d’quoi.

Le vent pince et la neige mouille,

Berçant, bercé.

Dans un chez-soi on a d’la houille

Ou du bois d’automn’ ramassé,

Berçant, bercé,

Bercé grenouille.

Dors, mon fieux, dors,

Bercé, berçant.

Fait froid dehors,

Ça glace l’sang.

Mais gna d’chez soi

Qu’ pour ceux qu’a d’quoi.

Not’ maison à nous, c’est ma hotte,

Berçant, bercé.

Et l’ vieux jupon qui t’emmaillotte

Jusqu’à ta chair est traversé,

Berçant, bercé,

Bercé marmotte.

Dors, mon fieux, dors,

Bercé, berçant.

Fait froid dehors.

Ça glace l’sang.

Mais gna d’chez soi

Qu’ pour ceux qu’a d’quoi

Ton bedon est vide et gargouille,

Berçant, bercé.

C’est pas pour nous qu’est la pot-bouille

Ni le bon pichet renversé,

Berçant, bercé,

Bercé grenouille.

Dors, mon fieux, dors,

Bercé, berçant.

Ça glace l’sang.

Mais gna d’chez soi

Qu’ pour ceux qu’a d’quoi.

J’aurions seul’ment un p’tit feu d’motte,

Berçant, bercé,

T’y chauff’rais peton et menotte

Et ton derrièr’ d’ang’ tout gercé,

Berçant, bercé,

Bercé marmotte.

Dors, mon fieux, dors,

Bercé, berçant.

Fait froid dehors,

Ça glace l’sang.

Mais gna d’chez soi

Qu’ pour ceux qu’a d’quoi.

Mais non sur un clair olifant,

Quand on a la gorge meurtrie

Par l’hiver à l’ongle griffant.

Las ! avec un râle étouffant

Il est salué chaque année

Chez ceux qu’il glace en arrivant,

Ceux qui n’ont pas de cheminée.

Il paraît, la mine fleurie,

Plus joyeux qu’un soleil levant,

Apportant fête et gâterie,

Bonbons, joujoux, cadeaux, devant

Le bébé riche et triomphant.

Mais quelle âpre et triste journée

Pour les pauvres repus de vent,

Ceux qui n’ont pas de cheminée!

Heureux le cher enfant qui prie

Pour son soulier au nœud bouffant,

Afin que Jésus lui sourie!

Aux gueux, le sort le leur défend.

Leur soulier dur, crevé souvent,

Dans quelle cendre satinée

Le mettraient-ils, en y rêvant,

Ceux qui n’ont pas de cheminée?

Dont la face est parcheminée.

Faites Noël en réchauffant

Ceux qui n’ont pas de cheminée.