Gil Cowley: A Path to and from Atelier 17

The importance of narrative when it comes to enjoying art cannot be overstated. While esthetic delight is equally valid as a starting point, most of us who feel nourished by the arts, know that how and why we became engrossed with a work of art is equally important. The “discovery” of a work of art, is the proverbial salt of a good artistic dish. Which is why a closer look at the prints of Gil Cowley is such a wonderful case in point. I found that there were so many lovely and interesting stories to be associated with them. The starting point of this story is simple: I bought two prints at auction. They were boldly signed in pencil “Gil Cowley”. It was a modest purchase, so I didn’t think much of it, except for the fact that one of them looked like a psychedelic bamboo forest to me, and that I really liked it. Then a bunch more prints signed identically came up for auction, and I bought those. Then another few lots came up... Suddenly I was the owner of 30 works by Gilbert Henry Cowley.

It got me thinking and digging around until I found Mr. Cowley, now living happily retired in West Virginia. We got talking via email about these prints, about him and his work, and about his life. And Gil agreed to start sharing how he got to make the prints now in my possession. If you keep on reading this, not only will you get to know the story of these prints, which are associated with Cowley’s time in Paris, etching and printing at Atelier 17. You will also catch a glimpse of how artists become who they are, and how they stick with making art, or move on. Here goes. This is the story of an oeuvre created from the fall of 1963 to the spring of 1964 by an American artist living in Paris, and a bit of a look at the life of their creator, an artist named Gil Cowley.

Gil Cowley was born in Portland, Oregon, where he also grew up. He remembers enjoying drawing at a young age, designing posters to hang in his grade school hallways. A defining early influence on young Gil’s artistic trajectory, was his High School art teacher. Don Kunz (1932-2001) taught art at Grant High School for just a few years, but clearly left a mark. Cowley remembers how “in three years of his teaching there, he was able to garner approximately 12 Scholastic Magazine art school scholarship for his students, including one for me to attend the Art Academy of Cincinnati. He was such an amazing teacher, that we (his best students) all went to galleries together as a group… classical concerts…etc.”. Many of us, who are nourished by the arts, can relate with the joy of the encounter of a true mentor, someone who is so excited to grow, that they want those around them to grow just as quickly and strongly. Kunz was so motivated that he apparently went above the call of duty. In Cowley’s words: “(During) spare period I took advanced art and calligraphy classes. (Don Kunz) was a proficient calligrapher too (Lloyd Reynolds at Reed College was a major influence on him, and we all learned this classical art and good handwriting).”. Kunz went on to greater things, relocating to New York in the mid-1960s, probably hoping to make it into the “big league”. He taught calligraphy at the Cooper Union for 33 years. That he taught there for so long is a clear testament to his excellence. But we are getting off track.

Example of Don Kunz calligraphy

Cowley left Oregon state at age 18, to study at the Art Academy of Cincinnati (1959-1963). In the words of the artist: “My main instructor in Cincinnati and later in Cleveland was Julian Stanczak (1928-2017). Julian was a student of Josef Albers at Yale along with Richard Anuszkiewiscz and Conrad Marca-Relli. Also, an amazing teacher! He taught you to think. My major was painting, but I also did a lot of printmaking in Cincinnati, particularly lithography. Cincinnati was a city with German and Irish heritage and had many old-time printers, and the Academy inherited a lot of lithographic stones. My interests in Stanley William Hayter sprung from there, and I went to study with him upon graduation with the traveling fellowship I was awarded at the end of my studies.” (Wilder Traveling Award)

Julian Stanczak in his studio in 1965

And so, Gil went, leaving behind the Midwest that had been his home for 4 years, and the United States, to go live in Paris, France. His head brimming with artistic ideals learned over four years in Ohio, Cowley stepped into the famed walls of Atelier 17. Stanley William Hayter had started the studio in 1927, at the insistence of Alice Carr de Creeft, who wanted to learn engraving from him. With the help of his friend and mentor Joseph Hecht, Hayter set up a studio where a handful of artists could come and make prints for a couple of days a week. The studio moved around Paris until the onset on World War II, when Hayter transferred it to New York. These New York years burnished Hayter’s aura and that of his collaborative workshop throughout the States.

The advanced group works together at Atelier 17, circa 1955, photo by Martin Harris

By 1950 the atelier had moved back to Paris, and it attracted artists from all corners of the world, interested in learning intaglio from Hayter. However, as Hayter became older, he felt the collaborative spirit that naturally occurs when working with contemporaries, slipping away. While he continued to teach at the print shop regularly, he would designate younger “masters”, who would de facto run Atelier 17’s daily operations. When Gil Cowey arrived, this is how he experienced it: “Bill taught the newbies the color technique as well as burnishing and other techniques. He had a set sample test you had to master. I still have one he signed for me. I do not remember his wife Helen Philips coming into the workshop. It was his place. Krishna Reddy was the Master, but he was rarely there. I believe Eugenio Tellez was then the default master. Bill came often, usually once or twice a week, and often in random visits. The atelier was always busy and ran pretty much as a coop. Everyone pitched in for supplies as needed: acid, varnish etc. Oddly, we did not use rubber gloves in the acid baths as all US schools did. We just rinsed after we used them.”

DDrawing by Gil Cowley: At the Acid Tray at Atelier 17

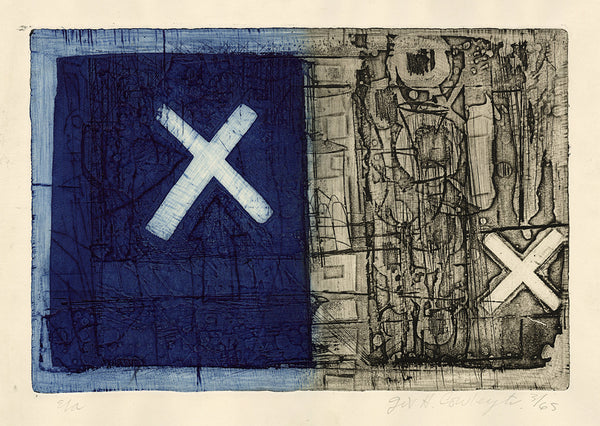

Cowley arrived in Paris ready to develop his printmaking skills. While training in Cincinnati, he had developed a strong visual language of abstraction in his paintings. He used gestural improvisation and simple symbols, such as circles and crosses, to structure these compositions. His vigorously drawn lines lent themselves well to various intaglio techniques.

By using aquatint, he could actually paint on copper with brushes, and drypoint needles gave him the ease of drawing similar to that of a pencil. And while he does not seem to have used the burin, favorite tool of Hayter, all that much, Cowley did etch his plates deeply. Printed on sturdy papers, these compositions’ inking is dimensional, truly rising above the surface of the paper. In raking light, the hidden side of ink lines catches a shadow.

Some of the memories Cowley shares about how he composed and printed shed light on the serendipity sought by printmakers who use simultaneous color printing, letting the press bring out the unexpected, all the while seeking technical excellence, to squeeze every bit of beauty out of their plates and inking. Cowley points to the use of unstructured drawing becoming part of compositions: “I just remembered that Hayter always used the phrase Automatic Writing, which he had taken from Andre Mason. I used the technique in some of my prints back then.”.

On the other hand, when it came to printing, the goal was one of quality, if also of the unexpected: “I did a lot of my prints on Van Gelder paper. I often hitch-hiked to Amsterdam to buy it (proverbial starving artist days). Arches I obtained in Paris, but Van Gelder was softer and seemed to wet better and take the impression more evenly.”

Cowley got busy in Paris. He etched and printed about 30 or so compositions in under a year. He also connected with a diverse group of artists. He reminisces: “The first language at the Atelier was English, Spanish was then second, and French came in at a close third. But truly French Canadians had a better chance with English than with French. The only person who could not communicate with anyone was a Finnish guy that only spoke Finnish. Pointing worked well.” Another vignette of time spent Atelier 17 is Cowley’s recollection of “a documentary the BBC did on Bill while I was there. I never saw it, but my future wife in England did. They were a pain in the you-know-what for a week or so. We avoided getting in the cameras’ way as much as possible and took a couple days off while they hogged the working spaces.” Cowley was clearly animated by a personal desire for growth while in Paris, rather than one of pursuing posterity. Cowley recounts: “I usually printed only a couple prints of each plate, and not full editions. I was more interested in making the art and seeing what I could do, rather than spend time printing up editions. I still have a lot of my plates from those days. I even sent one of my plates to a person in Gloucester, Massachusetts once. She had bought one of prints at an auction and had traced me down, probably hoping that it was a rare find and worth a lot of money.”

From the collection of Gil Cowley: Jim Hendricks, Vermont Pines 1960

The collaborative spirit found while hard at work at the workshop is apparent from the many testaments to long-lasting friendships and working relationships Atelier 17 alumni mention in their personal biographies. In the case of Cowley, not only did he move back to the States in 1964 with dozens of his own new works tucked under the arm, he had also traded prints with other artists who were working at Atelier 17 while he was there. In his flat files to this day, Cowley holds prints he traded with Bill Hayter, Gail Singer, Juan Downey, Tony Currell, Eugenio Tellez, Jon Hendricks, and others. These tokens of admiration, friendship, mutual respect show just how welcoming the atmosphere at Atelier 17 was. Young women and men were happy to share facilities and supplies, day-in day-out, providing input, sharing technical know-how, and swapping prints. So much for the famed ego of artists. Even in these later years, Atelier 17 was a horizontally integrated world, unlike almost any other in the world of art, anywhere and at any time. Cowley remembers his closest friends to be:

Jon S. Hendricks (American artist & famed Fluxus collection curator)

Tony Currell (British artist Anthony Currell who is now “retiered” (sic) in Sheffield, according to his LinkedIn profile)

Marcel-Henri Verdren (Belgian artist, 1933-1976)

Arun Bose from Dhaka (then British India, now Bangladesh, 1934-2007)

From the collection of Gil Cowley: Arun Bose, Cart, Paris 1964

While Cowley lost contact with all these friends, bound at the time by the passion for printmaking, these creative minds exchanged ideas, admired and encouraged one another, and traded prints in the studio.

Drawing by Gil Cowley: Portrait of Marcel Verdren

One such example of a personal friendship and of a collaborative spirit is best heard in the words of Cowley: “Marcel Verdren, who was a close friend, and I traveled to his home in Antwerp where I had mussels for the first time. Being from Oregon, I had seen sea gulls pry mussels from the shore and fly up in the air, then drop them on rocks to crack open and eat them. So, I always thought of them as just seagull food. I have loved them since then. Marcel instigated a group of us who were working at Hayter’s at the time. It was called the New International Gravure Group. This was meant to get a few gallery shows for us.”

Upon his return to the United States, Gil Cowley settled for another year in Ohio to obtain his BFA at the Cleveland Institute of Art. While there he did a bit more printmaking and a lot of painting. He then started his career as a well-rounded painter-engraver with portfolios brimming with art and a head full of ideas. At that time, he quickly gained exposure. About 50 of his paintings were exhibited at Baldwin-Wallace College and he found gallery representation with Far Gallery in New York City and Editions Electo in London, with incidentally at the time also carried the work of David Hockney. Both galleries carried his prints from the mid1960’s to the early 1970’s.

Mr. Shark from the Discovery Building gets Gil Cowley

By 1968 Cowley found work in television as an art director, first working for WJLA in Washington DC, which was then called WMAL. Cowley never looked back, and from then on worked in television art direction for the rest of his life, spending many years with CBS before moving on to work for the Discovery Network. In his words: “I was VP of Global Exhibits and Events for Discovery Communications Inc. We did some fun stuff, including mounting a giant inflatable shark on the Discovery Building. I did a lot of stage shows, trade shows, traveling museum show, press events, etc. We tried our hand at everything that was unexpected, all to create a “wow” effect. It was stimulating work! I was awarded over 200 industry honors while working in television, including an Emmy while at CBS and Silver Medal for illustration from the New York Art Director’s Club.”

Cowley’s shift from the world of fine art to that of art direction in television was however never complete. While the dynamic of living everyday life with its myriad obligations pushed painting and drawing into the background of his life, he never completely stopped putting pencil to paper and frequently would paint. Over the years, his artistic vocabulary evolved from one in which the gestural dominated to one in which signs, symbols and other assorted structural elements organized the space and dictated color and texture. In his paintings and drawings of the last few years ampersands and hashtags mark the canvas and paper in subtle ways.