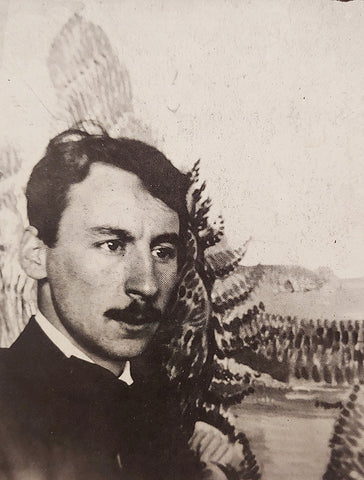

Joseph HECHT

A printer-friendly illustrated biography can be downloaded HERE.

Joseph Hecht was born on December 14, 1891 in Lodz (Poland, Łódź in Polish). At that time it was mostly an industrial city, especially strong in textile production. Samuel Hecht, the artist’s father, was a clothier who provided his wife, Joseph, and two daughters an affluent upper middle class life, with respected standing in the Jewish community. That community represented approximately 30% of the city’s population at the time. Joseph did his military service in an elite regiment of the Czar’s army. That part of Poland had been under Russian rule since the partition of Prussia. He did not last long in the service, and was sent home quickly. At age 18 he entered the Academy of Fine Arts in Cracow (a.k.a Matejko Academy of Fine Arts, in Polish Akademia Sztuk Pięknych w Krakowie im. Jana Matejki). His talents developed successfully, with medals of distinction won in 1912, 1913 and 1914. Hecht also was able to travel to Europe multiple times, supported financially by his father to visit Vienna in 1911 as well as Rome and Capri in 1913.

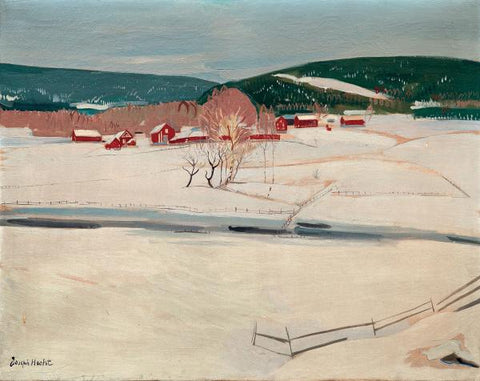

At the onset of World War I Hecht found himself visiting Berlin. Shown his medals of honor, which bore the effigy of the Emperor of Austria Franz Joseph, the German authorities are said to have given Hecht 48 hours to leave Germany for Norway, which had stayed neutral at the start of the conflict. He was forced to stay there in exile for the duration of the war. Little is known of his time in Norway. He painted, and produced some prints. He is known to have lived in Asker, a coastal town near Oslo. However, it is also assumed that he did not have much financial security. He befriended Johan Frederik Kroepellien, a patron of the arts who bought paintings from the artist. He also became friends with the Swedish painter Isaak Grünewald, who painted the portrait of Hecht (whereabouts unknown). These acquaintances led to a few exhibitions, including one in Bergen and one in Oslo at the Kunstforening.

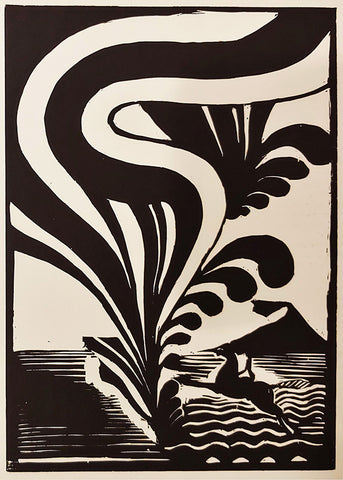

Technically the artist must have been limited in what he could create while in Norway. Painting was definitely an option, and oils with Norwegian landscapes have survived. Hecht also took up printmaking techniques. While he had been etching in Cracow, in Norway he picked up the drypoint and also carved some woodcuts. It is unclear where Hecht would have had access to tools and a press. Many of the 20 or so prints created in Norway were not editioned and never surface. A few of the drypoints were printed in editions of circa 30; this likely was done after the fact, maybe once Hecht had settled in Paris a few years later.

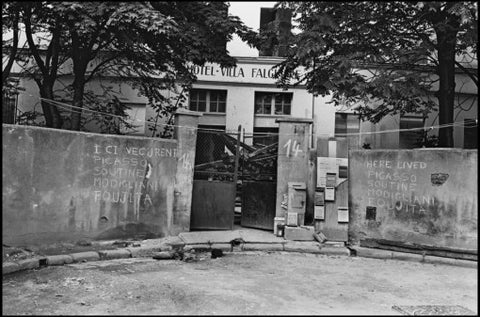

It seems Hecht returned to Italy right after the end of the hostilities, maybe in search of happier times. He may have spent up to two years in Italy, though traces of this part of his life no longer remain, to our knowledge. What is known is that at some point in the late 1910s or early in the 1920s Hecht arrived in Paris, where he immediately found a network of artist friends in the Polish, Russian and stateless Jewish communities which had flocked to the City of Lights after the end of the war. Thanks to Moïse Kogan, a sculptor, Hecht was assigned a studio at the Hotel Villa Falguière (14 Cité Falguière), a cul-the-sac where many artists had set up shop. This was steps from La Ruche, where the likes of Amedeo Modigliani and Jacques Lipchitz had their studio.

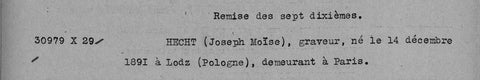

It is sometimes said that Hecht became French right upon his arrival. This is untrue. A record of his naturalization is kept at the Archives Nationales which attest to this happening in 1929.

Soon after arriving in Paris, Hecht met Ingrid Sofia Morssing, with whom he had a son, Henri, born March 27, 1922 (Henri Joseph Hecht, a.k.a. Henri Maïk). He married her shortly thereafter. It seems Morssing came from a wealthy Swedish family and may have come to Paris to study art. Little is known about his wife, but it is possible that Hecht’s ability to live in Paris was financed in part by his wife’s family and by his own. Surely, finding ways to make a living as an artist in Paris after the war, especially one who spoke little or no French, much have been arduous. His first steps towards being exhibited came through membership in the Salon d’Automne, of which he became a member in 1920, and then of the Salon des Indépendents.

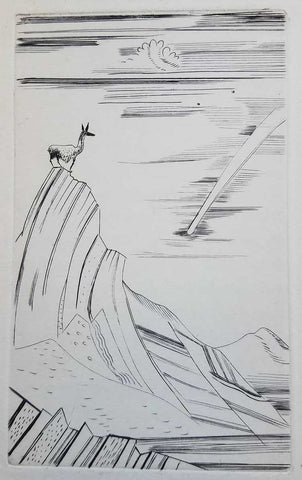

It is in 1926 that Hecht truly started to make a name for himself. He illustrated with 5 engravings a book titled L’Eubage aux antipodes de l’unité by Blaise Cendrars. This text was written for Jacques Doucet, the famed clothing designer and art collector, who may very well have been the one to commission these prints. Hecht and Doucet had been acquainted through mutual friends. That same year a solo show of Hecht’s work was held at the gallery of Berthe Weill and a few months later, another solo show was held at Galerie le Nouvel Essor. This latter show was to present Hecht’s album depicting the Ark of Noah. L’Arche de Noé, with a preface Gustave Kahn was very well received and sold successfully. Hecht’s career was now launched, and the album format seemed to work particularly well for his work.

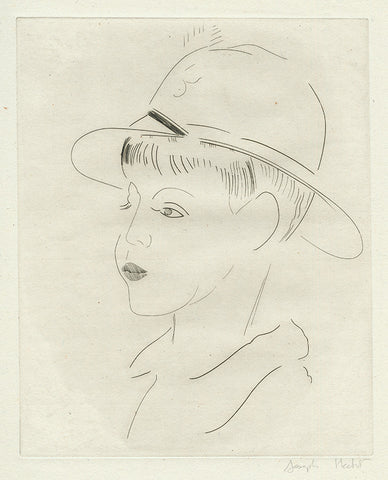

He published Atlas in 1928 (7 plates), Animaux as well as Croquis d’Animaux in 1929, each containing ten plates. The engravings he made for these albums, especially for the latter two, are regarded as the essence of Hecht’s oeuvre. Elegant lines depict mostly exotic animals, which Hecht sketched at the Jardin des Plantes. He went to Paris’ zoo to draw frequently, and on occasion some of his sketches still surface on the market. These drawings inspired him to refine the bodies of the animals to their essence. He rendered them with simplicity in a somewhat naïve style.

In 1926, as Hecht was finally starting to establish his career in Paris, he met Stanley William Hayter, likely through their mutual acquaintance of Alberto Giacometti (though it is sometimes said they met at Académie Julian). They became lifelong friends. And while they also were very different artists, it is known that Hayter learned much of his early technical skills as an engraver and as a printmaker from Hecht. The latter is said to have encouraged his friend to set up a printing studio, first in his own atelier (in 1927), and eventually at 17 rue Campagne Première: the famed Atelier 17 was born.

Then, in 1930, with the camaraderie of artists such as Pierre Guastalla, André Jacquemin and Louis Jospeph Soulas, to name but three, Hecht helped found an association of artists named La Jeune Gravure Contemporaine (The Young Contemporary Printmakers). He remained a contributor to the association’s exhibitions annually and supported it whichever way he could for the rest of his life.

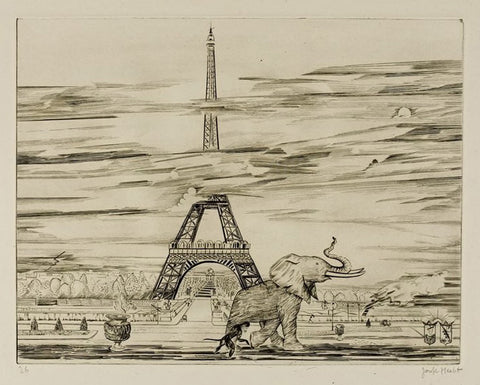

Upon returning from a trip to San Francisco (article in the San Francisco Examiner, March 5, 1933) Hecht published his fifth portfolio, another set of 10 engravings titled very simply Paris. Some of his most famous compositions, such as his Tour Eiffel and his depiction of the animals escaping the zoo in Rue Cuvier are part of this set.

But we can suppose that, despite the constancy of the style people had come to expect of Hecht, he liked to vary his artistic expression. While the 1920s were a time when the artist established himself in Paris, both professionally and as a father and husband, it seems that the 1930s were artistically more varied. Hecht definitely painted, and subjects include an array of topics: city views, landscapes, still lives.

At some point early in the 1930s he also made around a dozen cast bronzes of animals. These are sometimes said to be from the end of the 1930’s, but judging from earlier photographs this seems unlikely. These sculptures are scarce. His prints were also more varied during that phase of his career, and good many are not part of any sets. This first half of the 1930s was for the artist a period of discovery. We can suppose it may have been due to financial stability, though there is no proof of that per se, aside from Hecht’s artistic recognition.

On September 8th 1935 Hecht’s wife Ingrid died, leaving him to take care of his 13 year old son. It is unclear exactly how Hecht or Henri reacted to this tragedy, or how things evolved between father and son. It is likely that he did take care of his son quite closely. Henri Hecht, who eventually changed his last name to Maïk, is known to have printed some of his father’s later work, which indicates at the very least a working professional relationship. In May 1937 Hecht remarried a Swedish sculptor, Dana Bilde (1889-1975). That same year Hecht participated in the 1937 Exposition Universelle in Paris. He is said to have been awarded two gold medals.

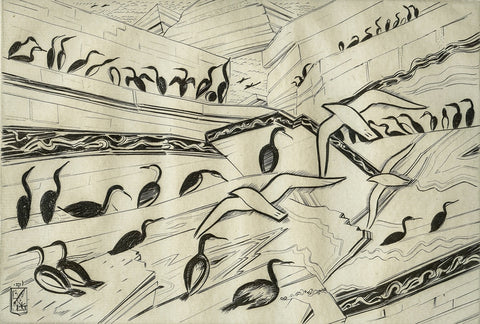

Circa 1938 Hecht reconnected with the portfolio format which had served him so well early in his career. In 1938 he published another very elegant set of animals titled Nouveaux Croquis d’Animaux. This set of 10 engravings is followed by another one titled Londres which contains 12 engravings depicting the English capital. Around the same time he printed one final set as well; this one titled Ile des Cormorans. It depicts cormorant birds in various states of abstraction. Hecht observed these seabirds on Ile de Rê, in the Atlantic, where he sometimes vacationed. The latter two sets were printed and published circa 1938-39. It seems they can’t have been major commercial successes, as the Second World War was about to erupt. It is also not completely clear that they were printed in full. The catalog raisonné of Hecht’s prints tries to make some sense of these editions, but this seems to be an attempt at clarity based on his son’s recollections and notes. These later sets are rather scarce.

On June 18, 1941 the artist left Paris, first supposedly for Casablanca, then to Marseilles, before finally settling in a hamlet by the name of Magnieu, near Belley, in the Savoie region of France, which was not occupied by Nazi Germany during the Second World War. Being Jewish he had no choice but to leave his life behind once again. His son Henri had meanwhile volunteered in the French Navy and been captured. This surely worried the artist. However, Henri was released and worked in Normandy as a lumberman from 1942 until the liberation. His wife may have resided in Grand Village on the Island of Oléron, though we were unable to verify this information. What is certain however, is that Hecht’s family structure was splintered to a point that must have led to a sense of loneliness. In the Savoie he was able to reconnect with other artists, mostly Jewish, who were also guests or visitors of his host (a man named Pranard, whom we were unable to identify).

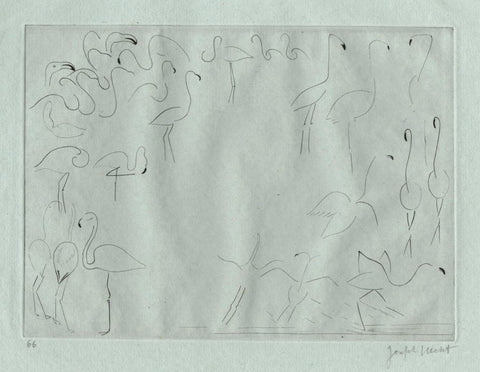

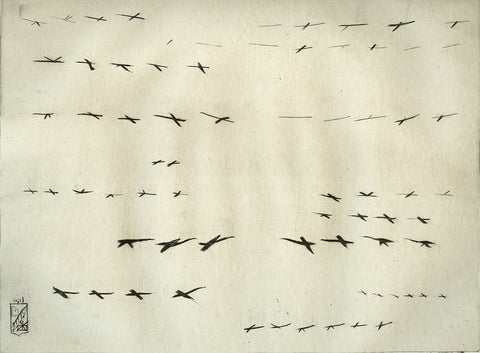

When Hecht returns to his Parisian studio, which had apparently remained intact, probably thanks to the care of his wife, he is said to have been feeling low and that he had a hard time getting back to work. While a depressive mood can surely be assumed, Hecht’s output seems to contradict his inability to work. Between the fall of 1944 and the end of his life he created a further 50 prints, some of which to illustrate three books, La Table Ronde (1945), Mauvaise Epoque (unpublished) and Quelques aventures de Maître Renart (1950). Hecht also created a print titled La Noyée in collaboration with Bill Hayter, and he invented a new way of creating compositions. These prints, made from copper plates he had engraved earlier in his career and which he cut out to keep only the animals, were inked and printed in spontaneous and varied arrangements. They are called découpages (cut-outs), gaufrages (dry stamping) or estampages (stamping or estampage). Hecht himself may have designated them as gravure mobile (mobile printmaking). These works are charming, and scarce.

On July 19, 1951 Joseph Moïse Hecht, who was getting ready to leave for Sweden to work on a commission of tapestry designs, died of a heart attack in his studio. His estate eventually went to his son.